Introduction

This is my summary for the RIS515 course. I have structured this course using the Risk Governance framework and the ‘learning aims’ that have been described in the first lecture.

Learning aims

- 📚 Basic knowledge about risk perception, risk communication, and risk governance.

- 🤝 Knowledge of social processes through which risks are defined.

- ❓ Why some risks are seen as acceptable and others not.

- 🚧 How causes of accidents and disasters are constructed.

- 📜 How policies to control risks and manage crises are developed.

- 🌐 Understanding of ways in which risk and culture, power, and trust are related.

- 🌍 When focusing on international and global issues, be able to apply the theoretical approaches on risk problems in society.

- 🧐 Have a critical perspective on risk and be able to communicate problems and dilemmas associated with risks in society.

(9.) Safety vs Security is not mentioned in the learning aims, but is part of the curriculum (Lecture 13-10-2023).

Compulsory reading

The course consists of the following compulsory reading material. For two of these articles, I have made separate summaries.

- Book: “Risk Governance: Coping with Uncertainty in a Complex World” by Ortwin Renn, 2017.

- Book: “Risk” by Deborah Lupton, 2013 (2nd edition).

- Article: “Perception of Risk” by Paul Slovic, published in Science (American Association for the Advancement of Science) in 1987.

- Article: “Risk as Analysis and Risk as Feelings: Some Thoughts about Affect, Reason, Risk, and Rationality” by Paul Slovic, Melissa L. Finucane, Ellen Peters, and Donald G. MacGregor, published in Risk Analysis in 2004.

- Book Chapter: “Differences in Risk Perception Between Hazards and Between Individuals” by Vivianne H. M. Visschers and Michael Siegrist, from the book “Psychological Perspectives on Risk and Risk Analysis,” published in 2018.

- Book: “Thinking, Fast and Slow” by Daniel Kahneman, 2012. (first 10 hours audiobook)

- Article: “The Social Amplification of Risk: A Conceptual Framework” by Roger E. Kasperson, Ortwin Renn, Paul Slovic, Halina S. Brown, Jacque Emel, Robert Goble, Jeanne X. Kasperson, and Samuel Ratick, published in Risk Analysis in 1988.

- Article: “Is Crisis Management (Only) a Management of Exceptions?” by Christophe Roux-Dufort, published in the Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management in 2007.

- Article: “The Conceptual and Scientific Demarcation of Security in Contrast to Safety” by S. H. Jore, published in the European Journal for Security Research in 2017.

Flashcards

Risk Governance Framework

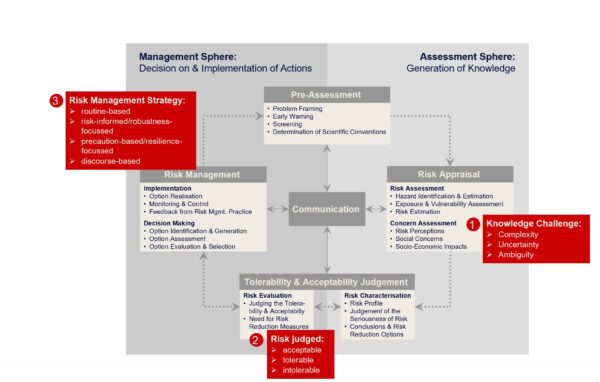

The Risk Governance Model is a structured framework used to manage and mitigate risks in various contexts. It includes the identification, assessment, and control of risks, as well as decision-making processes to minimize the potential impact of uncertain events on an organization or system. This model aims to enhance risk awareness, improve decision quality, and ensure effective risk management.

Navigate through this page using the figure below.

Pre-Assessment

The pre-assessment phase in the Risk Governance framework serves as the initial step in understanding and addressing risks. This phase plays a crucial role in shaping the course of risk governance by framing and defining the problem and specifying the terms of reference. It serves as an interface between knowledge and societal values, ensuring that the goals, objectives, and contextual conditions are considered while taking into account existing knowledge about the hazard and its potential impacts.

During pre-assessment, the selection and interpretation of phenomena as relevant risk topics are examined, a process known as “framing.” This involves identifying what major societal actors, such as governments, companies, the scientific community, and the general public, perceive as risks and risk problems. It is essential to understand that different actor groups may have varying perspectives on what constitutes a risk, and consensus depends on the legitimacy of the selection rule.

The pre-assessment phase also involves the institutional means of early warning and monitoring, where institutions in government, business, or civil society identify unusual events or phenomena to detect emerging risks and gain insights into their severity. It also addresses the need for monitoring recurring or newly evolving risks and highlights the importance of communication and coordination in early warning and monitoring activities.

In summary, the pre-assessment phase is a critical step in the Risk Governance model, focusing on framing the risk issue, understanding societal values, and establishing early warning and monitoring mechanisms to inform subsequent assessment and management processes.

Risk appraisal

Risk appraisal involves assessing risks comprehensively by considering both scientific assessments of risks to human health and the environment and the scientific assessment of related concerns, social implications, and economic factors. This phase of the framework is dominated by scientific analyses, including natural/technical sciences and social sciences such as economics. It consists of two stages:

- Scientific Assessment of Risks: Natural and technical scientists provide the best estimates of the physical harm that a risk source may cause. This involves assessing the hazard associated with the risk.

- Scientific Assessment of Concerns and Implications: Social scientists and economists analyse the concerns of individuals and society related to the risk. They also evaluate the social and economic consequences, including financial and legal implications and social responses like political mobilization.

The goal of risk appraisal is to produce a scientifically informed understanding of the physical, economic, and social consequences of a risk source. This step is crucial for making informed decisions about risk management and should not be confused with direct stakeholder involvement, which typically comes later in the risk governance process. Risk managers need to consider both aleatory (random) and epistemic (knowledge-based) uncertainties when conducting risk assessments.

Knowledge Challenge

The challenges of complexity, uncertainty, and ambiguity are related to the state and quality of knowledge available about hazards and risks rather than the intrinsic characteristics of the risks themselves.

- Complexity: Complexity refers to the difficulty of identifying and quantifying causal links between various potential causal agents and specific observed effects. It arises from factors such as interactive effects among these agents, long delays between cause and effect, interindividual variation, and intervening variables. Complex risks are challenging to assess because they require sophisticated modeling, and sometimes the cause-effect relationships are not intuitively evident. However, once resolved, complex risk assessments can provide a high degree of confidence in the results. For example, a highly complex risk might involve the interaction of multiple factors in the human body’s response to a drug, including age, genetics, diet, and more. These interactions make the assessment more intricate.

- Uncertainty: Uncertainty arises from incomplete or inadequate reduction of complexity in modeling cause-effect chains. It reflects the inherent incompleteness and selectivity of human knowledge. There are different components of uncertainty, including target variability, systematic and random errors in modeling, indeterminacy or stochastic effects, system boundaries, and ignorance or non-knowledge. Some of these components can be reduced through improved knowledge and better modeling tools, while others remain unresolved. For example, uncertainty could involve the variability in responses to a drug across different populations, the lack of knowledge about potential side effects, and the unpredictability of individual responses.

- Ambiguity: Ambiguity refers to differences in how different stakeholders or actors interpret and value information about risks and concerns. It can be divided into interpretative ambiguity, where different interpretations of the same assessment result exist, and normative ambiguity, where differing concepts of what is considered tolerable or ethically acceptable arise. Ambiguity often results from disagreements over values, priorities, assumptions, or boundaries used in defining possible outcomes. An example of ambiguity could be a disagreement over whether a minor physiological response to a chemical should be considered an adverse effect or just a bodily response without health implications. This disagreement could lead to different interpretations of the risk’s significance.

Tolerability & Acceptability Judgement

- Risk Characterization:

- Risk Profile: This step involves creating a detailed description of the risk, including its nature, potential hazards, exposure pathways, and other relevant characteristics. It essentially provides a comprehensive overview of the risk.

- Judgment of the Seriousness of Risk: In this part, the severity or seriousness of the risk is assessed, often considering factors like potential harm, consequences, and likelihood. It aims to understand how severe the risk could be.

- Risk Evaluation:

- Judging the Tolerability & Acceptability: This phase involves assessing whether the risk is tolerable and acceptable. It’s a critical step where the risk is evaluated based on societal and individual values, ethical considerations, and stakeholder preferences.

- Need for Risk Reduction Measures: If the risk is found to be intolerable or unacceptable, this step identifies what risk reduction measures are necessary. These measures aim to mitigate the risk and make it more acceptable.

- Acceptable: This means that the risk is deemed within acceptable limits, and no immediate or major action is required. It can be managed without significant changes.

- Tolerable: The risk is considered manageable but may require some risk reduction measures to ensure it remains at an acceptable level.

- Intolerable: If the risk is deemed intolerable or unacceptable, it signifies that significant actions are necessary to reduce the risk to acceptable levels.

Risk Management

Implementation:

Option Realization: In this sub-phase, the selected risk management options are put into action. This involves the practical implementation of strategies and measures designed to mitigate or manage identified risks.

Monitoring and Control: Continuous monitoring and control mechanisms are established to track the effectiveness of implemented risk management options.

Feedback from Risk Management Practice: Feedback loops are crucial for learning from experience. This sub-phase involves gathering insights and lessons from the practical application of risk management measures, providing valuable information for future decision-making and adjustments.

Decision-Making:

Option Identification and Generation: The decision-making process begins with identifying and generating various options or strategies for managing the identified risks. This involves creative thinking and consideration of a range of potential approaches.

Option Assessment: Once options are identified, a systematic assessment takes place. This involves evaluating the feasibility, effectiveness, and potential outcomes of each option.

Option Evaluation and Selection: Based on the assessments, the most suitable risk management options are selected. This involves a careful consideration of the trade-offs, costs, benefits, and overall alignment with organizational objectives.

Communication

Risk communication, as defined by the FDA Risk Communication Advisory Committee, involves interactively sharing risk and benefit information with the public to empower individuals to make informed, independent judgments. Within the Risk Governance Framework, risk communication is a component that plays a role within all the stages of the Risk Governance Framework.

Risk Communication Styles:

Top-Down: Traditional communication where information is disseminated from authoritative sources to the public.

Dialogue: Interactive and two-way communication involving engagement and feedback from the public.

Bottom-Up: Involves grassroots initiatives and community-driven communication.

Challenges in Risk Communication:

Social/Amplifications/Attenuations: Communicating risks is complicated by the social context, where public perception can be either magnified (amplified) or diminished (attenuated) based on prevailing attitudes, beliefs, and cultural influences.

Narratives: The use of stories and narratives in risk communication introduces a challenge as the interpretation and impact of information can vary significantly depending on the framing and storytelling techniques employed.

Deliberation: Encouraging informed and thoughtful discussions, or deliberation, about risks poses a challenge, as it requires time, resources, and a willingness among stakeholders to engage in open and constructive dialogue.

Optimistic Bias: Addressing optimistic bias is a challenge as individuals tend to perceive themselves as less vulnerable to risks compared to others, potentially leading to a underestimation of personal risk.

Trust/No Trust: Establishing and maintaining trust in risk communication is crucial, but the challenge lies in navigating situations where trust may be lacking or where there is a fundamental distrust in the information source, impacting how the message is received.

Baruch Fischhoff’s developmental stages

Baruch Fischhoff’s developmental stages, proposed in 1995, outlined a framework for understanding how individuals process and perceive risks. In this context, effective risk communication involves a strategic approach that aligns with these stages:

To begin, it is crucial to get the numbers right, ensuring that the information presented is accurate, reliable, and based on sound scientific evidence. Subsequently, it is important to tell them the numbers, conveying the quantitative aspects of the risk in a clear and accessible manner. Following this, efforts should be made to explain the numbers, providing context and meaning to the statistical information to enhance comprehension.

Furthermore, effective risk communication involves explaining what we mean by the numbers, elucidating the implications and real-world consequences associated with the presented data. To foster acceptance and understanding, it is beneficial to show them that they have accepted similar risks in the past, drawing parallels to familiar situations and experiences.

Additionally, the human element plays a pivotal role. It is essential to treat them nicely, recognizing the emotional dimensions of risk perception and approaching communication with empathy and respect. Lastly, fostering collaboration is key; it is advantageous to make them partners in the risk management process, involving the public in decision-making and empowering them to contribute to solutions.

Leave a Reply