The groupwork questions are likely to be part of the exam. Most questions are answered using four steps (Definitions, Different approaches, Discussion, and Conclusion) as recommended by the lecturer.

”Explain in such a way that your answer can be understood by a student that is not taking this course”.

Week 4 Group Work

Listen to Week 4 Group Work

Question 4-1: How much weight should be given to the uncertainties?

The importance assigned to uncertainties depends on the decision-making context. In situations where expected outcomes have a minor impact and occur frequently, lesser emphasis on uncertainties may be justified. Conversely, in safety-critical scenarios where the lack of investment could lead to severe consequences, such as the loss of life, a heightened consideration for uncertainties becomes imperative.

Economic Perspective:

In scenarios where the outcomes are frequent and impacts are minor, decision-making can lean heavily on economic theory, particularly the expected utility theory and portfolio theory.

- Expected Utility Theory: This theory posits that the decision that maximizes utility should be chosen. It involves calculating expected values by multiplying the outcomes (C) by their probabilities (P). This approach is effective when multiple investments can be conducted, allowing for the positive and negative outcomes to balance each other out over time.

- Portfolio Theory: This theory complements expected utility theory by suggesting that a diverse investment portfolio will even out the positive and negative outcomes. This approach relies on the law of large numbers and assumes that uncertainties can be managed by diversification.

Safety Perspective:

On the other end of the spectrum, in contexts with high uncertainty and the potential for extreme outcomes, such as managing the risk of a new type of nuclear energy facility, greater weight must be given to the precautionary principle. Here, the emphasis is on minimizing the potential for catastrophic outcomes, even if it means forgoing certain benefits.

- Cautionary Principle: This principle is crucial when the stakes are high, and uncertainties are significant. It requires decision-makers to consider the worst-case scenarios and prepare accordingly, without solely relying on cost-benefit analyses.

Dynamic Approach:

Given the wide range of decision-making contexts, a dynamic approach to weighing uncertainties is recommended. This approach recognizes that no single perspective is appropriate for all situations. Instead, the weight given to uncertainties should vary based on the specific context.

Layered – ALARP Principle:

The As Low As Reasonably Practicable (ALARP) principle exemplifies this dynamic approach. It involves a three-step decision-making model, where each step uses a different method to determine whether a risk-reducing or preventing measure should be implemented.

- Step 1: A crude analysis to determine if the costs are low and the benefits high. If the answer is yes, the measure is implemented.

- Step 2: A more detailed analysis, including an economic assessment (E[NPV]) and an Initial Cost of Averting a Fatality (ICAF) value. If this analysis indicates high costs or uncertainties, proceed to Step 3.

- Step 3: A qualitative analysis that includes uncertainty analysis and a Checklist for Robustness to evaluate the measure’s overall effectiveness and strategic considerations.

Conclusion:

The weight given to uncertainties in risk assessments should be tailored to the specific context. For contexts with low uncertainty and frequent outcomes, an economic perspective focusing on expected values and utility may suffice. In contrast, high-risk, high-uncertainty contexts demand a more precautionary approach. The ALARP principle offers a balanced, layered methodology that can adapt to various contexts, ensuring that both economic and safety perspectives are appropriately considered.

Question 4-2: Do you think the procedure is appropriate to use as basis for verification of ALARP? Give reasons for your opinion.

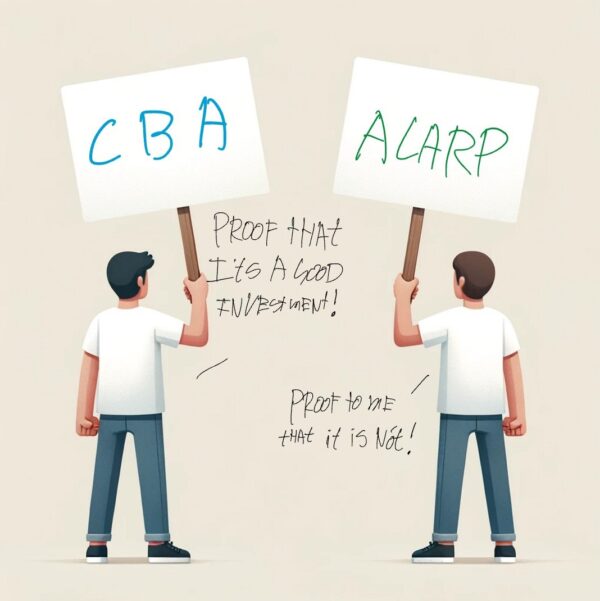

One way to implement ALARP and the grossly disproportionate criterion is by adopting a cost-benefit (cost-effectiveness) analysis. The costs can then be defined as grossly disproportionate to the benefits obtained if the expected cost is considered as x times higher than the expected benefit. The value of x is defined by the decision-makers and represents the disproportionate factor. Do you think the above procedure is appropriate to use as basis for verification of ALARP? Give reasons for your opinion.

Bottom Line Up Front (BLUF): Implementing ALARP and the grossly disproportionate criterion (GDC) can be useful in decision-making. However, the use of GDC should be dynamic and context-dependent.

Definitions:

ALARP: ALARP stands for “As Low As Reasonably Practicable.” It means that risk preventive measures should be taken as long as the costs associated with them are not grossly disproportionate to the benefits obtained.

Grossly Disproportionate Criterion (GDC): The GDC involves defining costs as grossly disproportionate if the expected cost (EC) is considered x times higher than the expected benefit (EX). The value of x is set by decision-makers and represents the disproportionate factor.

Cost-Benefit Analysis (CBA): CBA is an economic evaluation technique that compares the expected benefits (EX) with the expected costs (EC) of a decision, project, or investment.

Cost-Effectiveness Analysis (CEA): CEA compares the costs (EC) of achieving a specific outcome (EZ). It helps determine the most efficient way to achieve a desired result when multiple alternatives are available.

Discussion:

Static vs. Dynamic GDC: A fixed GDC value might not be appropriate in all contexts. The decision-making process should reflect the specific circumstances and nuances of each situation. A dynamic GDC allows decision-makers to adjust the factor based on the context, ensuring that the ALARP principle is applied effectively.

Limitations of Expected Values: Using expected values in risk assessment can oversimplify the representation of risks. Expected values tend to emphasize the average or most likely scenarios, potentially neglecting rare but severe events. Therefore, while CBA provides a structured approach, it must be complemented by an understanding of the underlying uncertainties to make informed risk decisions.

Approach for Implementing ALARP and GDC:

- Dynamic GDC: Implement a dynamic GDC that can be adjusted based on the context. This allows decision-makers to consider specific circumstances and ensure that the cost-benefit analysis remains relevant and practical.

- Layered Decision-Making Model: Employ a layered approach to decision-making, similar to the ALARP principle. This involves multiple steps to evaluate whether a risk-reducing measure should be implemented:

- Step 1: Conduct a crude analysis to determine if the costs are low and the benefits high.

- Step 2: Perform a detailed economic assessment, including the calculation of expected net present value (E[NPV]) and the Initial Cost of Averting a Fatality (ICAF).

- Step 3: Conduct a qualitative analysis, including uncertainty analysis and a robustness checklist, to evaluate the overall effectiveness and strategic considerations of the measure.

Conclusion:

The value of x in the GDC should not be a fixed, set value. A dynamic approach to the GDC is essential for effectively applying the ALARP principle in safety management. By considering the specific context and incorporating a comprehensive understanding of uncertainties, decision-makers can ensure that risk-reducing measures are implemented in a way that balances safety and practicality. This dynamic approach enhances the robustness of risk assessments and ensures that safety management decisions are well-informed and contextually appropriate.

Question 4-3: Explain How You Will Implement the ALARP Principle

Bottom Line Up Front (BLUF):

The appropriate method for implementing the ALARP principle is context-dependent, with a layered approach often providing the most comprehensive and adaptable solution.

Definitions:

ALARP: ALARP stands for “As Low As Reasonably Practicable.” It means that risk preventive measures should be taken as long as the costs associated with them are not grossly disproportionate to the benefits obtained.

HSE Requirements: Health, safety, and environmental prerequisites.

Decision-Making Context: The setting in which a risk decision is being made.

Risk Analysis: The process of identifying hazards and weighing the consequences of these hazards.

Risk: The combination of Consequences and associated Uncertainties (C, U).

Approaches for Verifying ALARP:

- Grossly Disproportionate Factor (GDF) with Static Value: In this method, a fixed GDF is used to determine if the expected costs (EC) are grossly disproportionate to the expected benefits (EX). This is typically done using a cost-benefit analysis (CBA), where if EC > EX * GDF, the measure is not implemented.

- Dynamic GDF: Here, the GDF is not static but varies based on the context and specifics of the decision. This allows for a more flexible approach, adjusting the GDF to fit the particular circumstances.

- Layered Approach: This is a more comprehensive method that involves multiple steps to determine if a risk-reducing measure should be implemented. This approach combines both quantitative and qualitative analyses and is considered the most thorough method for implementing ALARP.

Discussion of Approaches:

Cost-Benefit Analysis (CBA) with Fixed GDF:

- Pros: Simple and straightforward, provides clear decision criteria.

- Cons: Oversimplifies uncertainties, does not account for extreme outcomes, and requires transforming non-monetary values into monetary terms, which can be problematic.

DNV and Menon Approach:

- Pros: Puts more emphasis on uncertainties by considering best, worst, and most likely scenarios.

- Cons: Still relies on expected values, does not sufficiently address the strength of knowledge, and requires monetary valuation of non-monetary attributes.

Layered Approach:

- Step 1: Crude Analysis: A basic analysis to verify ALARP, asking if the costs are low and the benefits high. If yes, the measure is implemented without further analysis.

- Step 2: Detailed Analysis: If the first step is inconclusive, a more thorough risk analysis is conducted. This includes calculating the Expected Net Present Value (E[NPV]) and the Initial Cost of Averting a Fatality (ICAF). The ICAF is compared to the Value of a Statistical Life (VSL).

- Step 3: Qualitative Analysis of Uncertainties: This final step includes evaluating all other relevant aspects and uncertainties not covered in the previous steps. This involves considering public opinion, extreme outcomes, and the Strength of Knowledge (SoK).

Conclusion:

The layered approach is considered the best method for implementing the ALARP principle. This approach ensures a comprehensive evaluation by combining different methods and addressing the limitations of simpler models. It provides a holistic view of the risk landscape, considering uncertainties and non-monetary values, and is adaptable to different decision-making contexts.

By using the layered approach, decision-makers can ensure that risk-reducing measures are implemented effectively, balancing the need for safety with practical considerations of cost and benefit.

Question 4-4. Groupwork/Exam question: Explain why risk acceptance criteria are not consistent with the independence axiom of the expected utility theory

Bottom Line Up Front (BLUF): While risk acceptance criteria (RAC) can sometimes align with the independence axiom of expected utility theory, they are not always consistent. This inconsistency arises because RACs are fixed values set prior to decision-making, whereas the independence axiom is a general rule describing consistent risk-taking behavior.

Definitions:

Risk Acceptance Criteria (RAC): RACs are predefined thresholds that determine the level of risk considered acceptable in decision-making. They are fixed values set to limit the extent of acceptable risk, often used in safety and regulatory contexts.

Independence Axiom: This axiom is a principle of expected utility theory which posits that if an individual prefers one lottery over another, this preference should remain unchanged even if identical outcomes are added to both lotteries. It assumes that people stay consistent with their risk-taking preferences regardless of changes in the context or value of the outcomes.

Expected Utility Theory: Expected utility theory is a fundamental concept in economic decision-making. It suggests that individuals make choices based on maximizing their expected utility, which represents the satisfaction or value derived from an outcome.

Discussion:

Consistency Between RAC and Independence Axiom:

RAC and the independence axiom can sometimes be consistent. For example, if a decision-maker is risk-averse and has set a conservative RAC, their decisions may align with the independence axiom’s prediction that they will consistently avoid high-risk options. However, this alignment is not guaranteed because of the inherent differences in how RAC and the independence axiom function.

Inconsistency Between RAC and Independence Axiom:

- Fixed Value vs. General Rule:

- RAC: A fixed value set to define acceptable risk levels. It is established before evaluating specific scenarios and remains unchanged regardless of the context.

- Independence Axiom: A general rule that describes consistent behavior in risk-taking. It assumes that a person’s risk preferences remain stable even when the context or values change.

- Behavioral Consistency:

- RAC: Since it is a predefined threshold, a decision might be deemed unacceptable if it exceeds this value, even if the context or additional information suggests it could be acceptable.

- Independence Axiom: Suggests that an individual’s risk preferences do not change with context. For example, a person who is generally risk-averse will consistently avoid high-risk options, irrespective of slight changes in the situation.

- Practical Deviations:

- In practice, decision-makers might exhibit inconsistencies when faced with structurally similar lotteries. For instance, if an RAC favors a certain outcome in one scenario, introducing an identical outcome in a different context should theoretically not alter the preference. However, deviations from the independence axiom can occur, leading to changes in preferences despite common outcomes.

Example:

Consider a company with an RAC that states any project with a potential fatal accident rate (FAR) exceeding a certain threshold is unacceptable. If a new project has a FAR slightly above this threshold, it might be rejected regardless of other potential benefits. According to the independence axiom, if the decision-maker is risk-averse, their preference should remain consistent even if another similar project with a slightly lower FAR is considered. However, the rigid RAC might lead to different decisions in similar contexts, showing inconsistency with the independence axiom.

Conclusion:

Risk acceptance criteria (RAC) and the independence axiom of expected utility theory can sometimes align but are not inherently consistent. RACs are fixed values set to limit acceptable risk levels, while the independence axiom describes a general rule of consistent risk-taking behavior. The differences between a fixed threshold and a general behavioral rule can lead to inconsistencies in decision-making, particularly when structurally similar scenarios are evaluated differently due to the rigidity of RACs. Therefore, while RACs are useful for setting safety and regulatory standards, their inflexibility can sometimes contradict the principles of expected utility theory.

Week 6 Group work

Listen to Week 6 Group work

Question 6-1: Elaborate on how to conduct analyses of consequences, costs and benefits when introducing or modifying various HSE requirements and measures in the petroleum industry.

Button Line Up Front (BLUF)

Different methods can be used to conduct an analysis of consequences, costs and benefits when introducing or modifying various HSE requirements and measures in the petroleum industry. The right way of conducting these analyses is dependent on the decision-making context.

Definitions

HSE requirements: Health, safety and environmental prerequisites.

Decision-making context: The setting in which a risk decision is being made.

Risk analysis: The process of identifying hazards and weighing the consequences of these hazards.

Risk: The combination of Consequences and associated Uncertainties (C,U).

Methods

Different methods can be used to analyse the consequences, costs, and benefits of introducing or modifying HSE requirements in the petroleum industry. Within HSE, it is common to take an ALARP starting point when assessing risk. ALARP stand for As Low As Reasonable Practicable. This means that a risk-reducing measure should be implemented unless the costs are grossly disproportional to the benefits obtained. In other words, we can say that the ‘burden of proof’ is upon the decision-maker to show that the costs vastly outweigh the benefits. The next question, then, is, how do we determine whether a risk-reducing method is grossly disproportional? I will discuss three methods to do so, and then discuss and conclude on the most appropriate method for most decision-making contexts.

1. A Cost Benefit Analysis (CBA) with a fixed grossly disproportional factor (GDF).

The foundation of a CBA is the expected utility theory. This theory is the starting point of all economic thinking and states that the alternative with the highest expected utility should be chosen. The expected utility is often determined by calculating expected values. An expected value is the outcome of the consequences times its probability C*P. The rationale for using expected values as decision support is the portfolio theory. This theory states that if repeated investments are made, gains and losses will even out.

The classical CBA is the outcome of Expected Benefits – Expected Costs. Or in mathematical terms E[NPV] = EX-EC. Where E[NPV] stands for Expected Net Present Value, EX are Expected Benefits and EC are expected costs. We calculate ENPVs to make sure that we take into account the future value of money. After having conducted this analysis we have not yet determined that the investment would be grossly disproportionate to the benefits obtained. To do this, we can use a fixed grossly disproportionate factor. For instance, by saying that the expected costs cannot be 10 times higher than the expected benefits.

The problem with this approach is that uncertainties are not sufficiently taken into account. Expected values can only be fruitfully calculated when there is strong knowledge about the expected costs and benefits. This calculation alone does not tell us anything about this knowledge. Secondly, expected values do not represent extreme outcomes well. They just present the centre of gravity of a probability distribution. Which can lead to a misleading risk picture. Thirdly, if a risk-reducing measure is cheap to implement but not in line with the fixed grossly disproportionate factor, it can be disregarded unnecessarily. Lastly, this approach requires the transformation of attributes to monetary values. This can be problematic for HSE, as it is difficult to express environmental impact, health and the value of human lives in monetary value.

2. The DNV and Menon approach

The DNV and Menon approach shares similarities with the previous method, but multiple CBAs are conducted. First of all, a worst-case scenario is conducted by calculating a CBA with the lowest expected benefits and the highest possible expected costs. Secondly, a CBA is conducted with the most likely expected outcomes. Thirdly a CBA is conducted with the most positive outcomes, high expected benefits and low expected costs. These three outcomes are then compared to determine if the investment is grossly disproportionate.

This approach puts more emphasis on uncertainties, and can therefore be considered as better than the previous approach. Not all concerns mentioned with the previous method are addressed, however. We still use expected values, which do not express the uncertainties sufficiently. For example, there is no expression of the Strength of the Knowledge (SoK) used for the calculation. Secondly, this approach also requires the transformation of outcomes into monetary values, which can be problematic.

3. The Layered Approach

The last approach uses a combination of methods and is therefore considered to be the best approach for conducting an analysis of consequences, costs and benefits when introducing or modifying various HSE requirements and measures in the petroleum industry. The approach consists of three ‘layers’.

1. Crude analysis

In this step, a simple analysis is conducted to verify ALARP. The steps aim at answering the question are the costs low and the benefits high? If the answer is yes, the risk-reducing measure should be implemented. This prevents the need for a thorough analysis of investments that are clearly beneficial.

2. More detailed analysis.

If the first step does not yield clear results. A more thorough risk analysis is conducted. If the calculation expected values are sensible (see previous discussion), an E[NPV] and an ICAF value are Calculated. ICAF stands for the initial costs of averting a fatality. The outcome of this calculation can be compared to the value of a statistical life (VSL). Which is often already set by the industry. If the ICAF value is higher than this set value, or if the E[NPV] yields a negative result. We move on to the next step. If not, grossly disproportion can not be determined, and the risk-reducing measure should be implemented.

3. Analysis of other relevant aspects and uncertainties.

In this last step, all other relevant aspects are taken into account. Aspects that are not taken into account in the previous steps. For instance the public opinion upon the investment that is discussed. Uncertainties are also further analyzed. By looking at for example extreme outcomes and the SoK. This can be done by going through checklists.

If after this step, the investment is still considered to be grossly disproportional to the benefits obtained then the risk-reducing measure should not be implemented.

Conclusion

We have discussed three methods to conduct an analysis of consequences, costs and benefits when introducing or modifying various HSE-requirements and measures in the petroleum industry. The best method will be dependent on the decision-making context, but from the three methods discussed the layered approach will probably be the best approach. This approach paints a holistic picture of the risk landscape. It puts a larger emphasis on uncertainties by combining different quantitative and qualitative methods. Making it superior to the first and second method.

Question 6-2: To what extent should all the attributes be transformed to one comparable unit when evaluating safety measures?

Bottom line Up Front (BLUF)

Transforming all attributes to one comparable unit when evaluating safety measures can be beneficial to make it easier to compare different safety measures with each other. The attributes of safety measures are however difficult to transform into a single unit. Which can cause misleading decision support.

Definitions

Safety measures are risk-reducing investments that decrease harm.

An attribute of the safety measure can be seen as something that is related to the safety measure. For instance, the costs involved, the number of lives it could save or the time that is related to the execution of the safety measure.

A comparable unit can be seen as a value of measurement. For instance, euros, time or potential lives saved.

Methods and Discussion

There are different measures for evaluating safety measures. Examples of this are Cost Benefit Analysis (CBA), multi-attribute analysis, and ‘Layered approaches’ involving a combination of risk evaluation methods. Some of these methods require the transformation of attributes to one comparable unit. For instance when conducting a CBA. By transforming all attributes into one measure, safety invested can easily be compared to each other. Resulting in a clear picture of which investments yield the highest return.

The problem with this approach is that it is difficult to transform all attributes into one comparable unit. Which is in the case of a CBA, a momentary value. When talking about safety measures, we are concerned with reducing harm to humans. It is difficult to transform the value of life into a monetary value. Besides this, there are other attributes that are also hard to capture into a monetary value. For instance, the effects of safety legislation and public opinion. Lastly, when working with a (monetary) comparable unit, we make use of expected values. Expected values do not resemble the uncertainties of safety risks well. Expected values do not tell us for example how strong the knowledge is on which the calculation is made. Besides this, only the centre of gravity of the probability distribution is expressed. Putting too little emphasis on extreme values that might require more consideration.

To prevent these problems, it is best to use a combination of different methods. In this way, all the relevant aspects of a safety measure can be addressed. This could for example be by combining a multi-attribute analysis, in which different aspects of multiple safety measures are compared, with a CBA.

Conclusion

Transforming all attributes into a single value is a simplification of reality. This means that information gets lost. The extend to which this loss is acceptable to make an effective comparison of safety measures, is dependent on the decision making context. By using a combination of methods, including and excluding the transformation of attributes, a holistic image can be generated. Providing the best decision support.

Week 8 Group work

Question 8-1: What is the main difference between the traditional HFMEA and the one suggested in Abrahamsen et al. (2016)?

BLUF (Bottom Line Up Front)

The main difference between traditional HFMEA and the approach suggested by Abrahamsen et al. (2016) lies in the integration of uncertainties and the evaluation of control measures’ reliability.

Definitions

HFMEA (Healthcare Failure Mode and Effect Analysis): A risk analysis method adapted from FMEA, specifically designed to identify and mitigate potential failures in healthcare processes.

Different Approaches

Traditional HFMEA:

- Define the HFMEA Topic: Identify a high-risk or vulnerable area/process.

- Assemble the Team: Create a multidisciplinary team with subject matter experts.

- Graphically Describe the Process: Create a process flow diagram with subprocesses.

- Conduct Hazard Analysis: List potential failure modes, assess their severity and probability, and calculate a hazard score.

- Decide Actions and Outcome Measures: Based on the hazard score, determine if further action is required and document outcome measures.

Adjusted HFMEA (Abrahamsen et al. 2016):

Broader Risk Evaluation: Integrate the evaluation of uncertainties alongside severity and probability. Use a two-step procedure:

- Categorize combinations of probability and severity.

- Evaluate risks by considering uncertainties.

Broader Evaluation of Control Measures: Assess not just the existence but also the reliability and uncertainties of control measures:

- Identify existing control measures.

- Assess their effects and reliability.

- Evaluate associated uncertainties.

- Determine the overall performance of control measures.

Discussion

The traditional HFMEA is straightforward and effective for many healthcare settings but may lack depth in complex or highly uncertain environments. It primarily focuses on quantifiable aspects like severity and probability, potentially overlooking significant uncertainties and the nuanced performance of control measures.

In contrast, Abrahamsen et al. (2016) propose an HFMEA that addresses these limitations by explicitly considering uncertainties and the reliability of control measures. This adjusted approach aims to provide a more comprehensive risk assessment, crucial for environments where uncertainties are significant, such as in healthcare processes involving critical or emergency care.

For example, the adjusted HFMEA suggests evaluating not just the immediate effectiveness of control measures but also their long-term reliability and potential failure modes. This approach acknowledges that even highly effective control measures can fail under certain conditions, and those potential failures must be accounted for in the risk assessment.

Conclusion

The primary difference between traditional HFMEA and the adjusted approach by Abrahamsen et al. (2016) is the incorporation of uncertainties and a more thorough evaluation of control measures. While traditional HFMEA focuses on severity and probability, the adjusted HFMEA provides a more holistic view by considering the reliability and uncertainties of control measures. This leads to a more robust risk assessment, particularly in high-risk and complex healthcare settings.

Question 8-2: Explain briefly the practical approach for the evaluation of acceptable risk as described in Abrahamsen, Aven and Iversen (2009).

BLUF (Bottom Line Up Front)

The practical approach for evaluating acceptable risk, as described by Abrahamsen, Aven, and Iversen (2009), involves integrating safety management with uncertainty management to provide a more comprehensive risk assessment. This approach emphasizes the consideration of uncertainties alongside probabilities and expected values in the decision-making process.

Definitions

Risk Perspective: Risk is defined as a combination of events (A), consequences (C), and uncertainties (U). This perspective goes beyond traditional methods that primarily focus on probabilities (P) and expected values (E), incorporating uncertainties to provide a fuller risk picture.

Different Approaches

Traditional Approach:

- Focuses on calculating probabilities and expected values for risk assessment.

- Risk acceptance criteria are typically based on these calculated probabilities and expected values.

- Decisions are made based on whether these values fall within predefined acceptable limits.

Integrated Framework by Abrahamsen, Aven, and Iversen (2009):

Two-Dimensional Risk Concept:

- Events and Consequences (A, C): Identifies potential events and their associated consequences.

- Associated Uncertainties (U): Evaluates the uncertainties surrounding these events and consequences, recognizing that probabilities are conditional and subject to various assumptions.

Incorporating Uncertainties:

- Recognizes that calculated probabilities are based on background knowledge and assumptions, which can hide significant uncertainties.

- Uses a broader perspective to evaluate risks by not only the calculated probabilities but also the associated uncertainties.

Operational Hazard Identification (HAZID):

- Conducts a HAZID analysis early in the project stages to identify potential hazards and uncertainties in the current operations.

- Involves personnel from various operational roles to provide a comprehensive understanding of the risks and uncertainties.

Categorization of Uncertainty Factors:

- Uncertainty factors are categorized as high, medium, or low based on the conditions and their potential influence on risk indices.

- This categorization helps in understanding the impact of uncertainties on the overall risk assessment.

Discussion

The practical approach described by Abrahamsen, Aven, and Iversen (2009) highlights the limitations of traditional risk assessments that rely solely on probabilities and expected values. By integrating uncertainties into the risk evaluation process, this approach provides a more realistic and comprehensive assessment of risks.

For example, in the case of designing and operating flare and HIPPS systems, the traditional approach would focus on ensuring that the probabilities of overpressure incidents are within acceptable limits. However, by incorporating uncertainties, the integrated framework considers factors such as operational procedures, human factors, and system dynamics, which could influence the actual risk levels.

This broader perspective allows for a more nuanced decision-making process that accounts for potential surprises and hidden risks, leading to more robust and reliable safety management practices.

Conclusion

The main difference between traditional risk assessment methods and the practical approach described by Abrahamsen, Aven, and Iversen (2009) is the emphasis on incorporating uncertainties into the risk evaluation process. This approach recognizes that probabilities and expected values alone are insufficient for comprehensive risk assessment and that uncertainties play a critical role in understanding and managing risks effectively. By adopting this integrated framework, organizations can achieve a more realistic and reliable assessment of acceptable risks.

Question 8-3: Discuss the use of the VOI (Value of information) measure in a decision-making context.

BLUF (Bottom Line Up Front): The Value of Information (VOI) measure quantifies the benefit of obtaining additional information before making a decision, helping decision-makers determine whether the cost of acquiring new information is justified by the potential improvement in decision outcomes. It uses methods like EVPI, EVSI, and Bayesian approaches to assess and optimize decision-making across various fields.

Definitions

The Value of Information (VOI) is a quantitative measure used in decision-making to assess the benefit of acquiring additional information before making a decision. It represents the improvement in decision quality and potential outcomes that can be achieved by having more or better information. VOI is calculated by comparing the expected outcomes with the additional information to those without it.

Different Approaches

There are several approaches to calculating and using VOI in decision-making:

Expected Value of Perfect Information (EVPI):

- EVPI measures the maximum amount a decision-maker should be willing to pay for information that would remove all uncertainty.

- It is calculated as the difference between the expected value with perfect information and the expected value with current information.

- EVPI = Expected Value with Perfect Information – Expected Value without Perfect Information.

Expected Value of Sample Information (EVSI):

- EVSI estimates the value of information that is not perfect but comes from a sample or study.

- It assesses how much a decision-maker should be willing to pay for partial information.

- EVSI = Expected Value with Sample Information – Expected Value without Sample Information.

Bayesian Approach:

- This approach incorporates Bayesian statistics to update the probability distributions of uncertain parameters based on new information.

- It uses prior distributions and updates them with sample data to form posterior distributions, thus refining the decision-making process.

Decision Trees and Influence Diagrams:

- Decision trees and influence diagrams are visual tools that help in structuring and analyzing the decision problem, incorporating VOI to show the potential outcomes and the paths that lead to them.

- These tools help in visualizing the impact of acquiring additional information on the decision outcomes.

Discussion

VOI is crucial in a wide range of fields, including business, healthcare, and engineering. By quantifying the benefit of additional information, decision-makers can make more informed choices about whether to invest in gathering more data. For example:

- Healthcare: In medical decision-making, VOI can help determine the value of conducting additional tests or medical trials. By understanding the potential improvement in patient outcomes, healthcare providers can justify the costs and efforts associated with additional diagnostics.

- Business: In a business context, VOI can assist in market research decisions. For instance, before launching a new product, a company might use VOI to decide whether the cost of additional market surveys is justified by the potential for increased sales and reduced market uncertainty.

- Engineering: Engineers might use VOI when deciding on additional safety tests for new structures. The measure helps in balancing the cost of extra testing against the potential risk reduction in the structure’s performance.

Conclusion

The Value of Information is a powerful measure that aids in making better-informed decisions by quantifying the benefit of acquiring additional information. By utilizing approaches like EVPI, EVSI, and Bayesian methods, decision-makers can systematically evaluate whether the cost of obtaining new information is justified by the expected improvement in outcomes. VOI ensures that resources are allocated efficiently, reducing uncertainty and enhancing the quality of decisions across various fields.

Question 8-4: A Vision Zero of no fatal accidents has for many years been used as a safety management principle in the oil and gas industry. Recently the industry has taken the use of this principle a step further, moving from zero fatalities to zero production loss. Discuss the rationale for this principle.

BLUF (Bottom Line Up Front): The oil and gas industry’s shift from a Vision Zero of no fatal accidents to a broader goal of zero production loss reflects an attempt to enhance both operational safety and efficiency. However, this approach may not align with traditional risk management principles, which aim to balance the upsides and downsides of risks. Striving for zero production loss overlooks the need to manage risks in a balanced manner.

Vision Zero in the Oil and Gas Industry:

Vision Zero, a principle aiming to eliminate fatalities and hazardous incidents, has been a foundational aspect of safety management in the oil and gas industry since the 1990s. Initially focused on health, safety, and environmental (HSE) outcomes, the principle evolved in the early 2000s to include quality, forming the HSEQ framework. This expanded vision also introduced the concept of zero production loss, reflecting a shift towards integrating economic efficiency with safety management (Selvik & Aven, 2017).

Economic Motives and Risk Management:

The rationale for extending Vision Zero to zero production loss is rooted in its potential economic benefits. Unplanned production stoppages can lead to significant financial losses, making the goal of zero production loss highly attractive from a cost-efficiency perspective. This aligns with the broader strategic aim of maintaining continuous operations to maximize profitability and efficiency.

Risk management in this context involves balancing risk reduction with opportunity exploration. The principle of ALARP (As Low As Reasonably Practicable) guides this balance, emphasizing that risks should be mitigated until the cost of further reduction becomes disproportionate to the benefits gained. Cost-benefit analyses and Net Present Value (NPV) calculations are common tools used to assess whether the benefits of risk reduction measures justify their costs (Selvik & Aven, 2017).

Decision Making and Quality Management:

Incorporating zero production loss into Vision Zero ties safety directly to operational efficiency. This approach follows the Expected Utility Theory, advocating for decisions that optimize expected outcomes based on calculated risks and benefits. However, extending Vision Zero to encompass zero production loss raises critical questions about its rationality, which can be evaluated against four criteria: precision, evaluability, approachability, and motivation (Selvik & Aven, 2017).

- Precision: The goal must be clear and well-defined. While the aim of zero production loss provides a specific direction, it lacks a defined timeframe for achievement, making it less precise in practical terms.

- Evaluability: There must be clear metrics for evaluation. This criterion is satisfied, as production losses can be quantitatively measured, allowing for straightforward assessment of progress.

- Approachability: The goal must be feasible. While technological and managerial improvements can reduce production losses, achieving absolute zero is highly ambitious and may not be fully attainable in practice. The feasibility is further challenged by the fixed nature of many installed systems and the potential for new technologies to introduce additional failure modes (Selvik & Aven, 2017).

- Motivation: The vision should motivate decision-makers to allocate resources effectively. Although the economic incentives are strong, this focus might overshadow other critical safety concerns, potentially conflicting with broader risk management principles that balance cost and risk. The pursuit of zero production loss must consider the overall economic benefits and not just minimize production losses at the expense of other significant factors (Selvik & Aven, 2017).

Conclusion:

The extension of Vision Zero to include zero production loss represents an effort to merge safety with economic efficiency. While this goal aligns with maximizing operational continuity and reducing costs, it introduces significant challenges. The approach meets the evaluability and motivation criteria but falls short on precision and approachability. It risks oversimplifying complex risk management by focusing too narrowly on economic outcomes, potentially neglecting other crucial safety considerations.

In summary, while the economic rationale for zero production loss is compelling, it must be balanced with a comprehensive understanding of risk management principles. This ensures that safety strategies remain holistic and effective, addressing all aspects of risk rather than focusing exclusively on production metrics. The approach should incorporate realistic timeframes and acknowledge the practical limitations of achieving absolute zero production loss, ensuring that it does not undermine other important safety and operational concerns.

Week 11 Group work

Listen to Week 11 Group work

Question 11-1: What is the main difference between a safety-oriented bubble diagram and a risk plot?

BLUF (Bottom Line Up Front): A Risk Plot shares similarities with the Bubble Diagram. But has one distinct difference. The consequences are represented in a 90% confidence interval. This means that the assessor is 90% certain that the severity of the consequences are within the given bracket.

Definitions

A Bubble Diagram is a graph that visualizes three aspects of risk.

- The probability of an event occurring is represented on the y axes.

- The severity of the consequences is represented on the x-axis.

- The SoK is represented by the size of the bubbles

A Risk Plot shares similarities with the Bubble Diagram. But has one distinct difference. The consequences are represented in a 90% confidence interval. This means that the assessor is 90% certain that the severity of the consequences is within the given bracket.

Discussion and Conclusion

The main difference between them: Risk plots are more precise in reflecting important aspects of risks than bubble diagrams, while bubble diagrams are considered to give a better basis for ranking between risks (Abrahamsen et al., 2014, p. 207).

Question 11-2: Explain briefly on how you will visualize and communicate the results from a risk assessment to the decision-makers.

BLUF (Bottom Line Up Front): The right method for visualising and communicating risks from a risk assessment depends on the decision-making context. A combination of tools, tailored to its audience should be used to express both the consequences and uncertainties of risks.

Definitions

Risk Assessment: A systematic process for identifying and evaluating potential risks that could negatively impact an organization’s ability to conduct business.

Risk Visualization: The process of representing risk data graphically to aid understanding and decision-making.

Communication of Risk: The process of conveying risk information to stakeholders to inform decision-making.

Different Approaches

- Risk Matrices: Traditional tools that plot the likelihood of an event against its impact. While easy to use, they often oversimplify risk and do not adequately capture uncertainties or the strength of the underlying data.

- Bubble Diagrams: These represent risk events with bubbles where the size of each bubble reflects the level of SoK. They use the x-axis and y-axis for probability and consequence, respectively, and bubble size for SoK levels (high, medium, low).

- Risk Plots: A Risk Plot shares similarities with the Bubble Diagram. But has one distinct difference. The consequences are represented in a 90% confidence interval. This means that the researcher is 90% certain that the severity of the consequences are within the given bracket.

Discussion

Risk Matrices are simple and widely understood but have limitations in conveying the complexities and uncertainties of risk data. According to Cox (2008), risk matrices can mislead decision-makers by not fully representing the underlying uncertainties and by simplifying the risk into broad categories that might not reflect real-world complexities.

Bubble Diagrams address some of these limitations by incorporating the uncertainty dimension directly into the visualization. According to Abrahamsen et al. (2011), these diagrams provide a better basis for ranking risks by showing how uncertainty affects risk assessment outcomes. However, they still rely on expected consequences, which might not capture the full range of potential outcomes.

Risk Plots, as suggested by Aven (2013), take visualization a step further by using prediction intervals for consequences and a strength-of-knowledge dimension. This method provides a more accurate reflection of the uncertainties involved in risk assessment. The use of a 3D approach allows decision-makers to see not only the likelihood and impact of risks but also how confident the assessors are about these estimates.

Conclusion

To effectively visualize and communicate the results from a risk assessment to decision-makers:

- Use a Combination of Tools: Start with risk matrices for a broad overview, but also incorporate bubble diagrams and risk plots to provide a deeper understanding of uncertainties and the strength of the underlying data.

- Highlight Key Metrics: Ensure that visualizations include probabilities, consequences, and a clear indication of uncertainty or strength of knowledge. This helps decision-makers grasp the full scope of the risk landscape.

- Simplify without Oversimplifying: While it’s important to make the information accessible, avoid oversimplification that can lead to misunderstandings. Use detailed annotations and explanations to accompany graphical data.

- Tailor Communication to the Audience: Different stakeholders might require different levels of detail. Customize your risk communication to address the specific needs and expertise of your audience.

By combining these methods, you can provide a comprehensive and clear visualization of risks that aids in informed decision-making, ensuring that all relevant factors, including uncertainties, are considered.

Question 11-3: To what extent is the uncertainties visualized in a traditional risk matrix?

BLUF (Bottom Line Up Front): Traditional risk matrices generally do not visualize uncertainty. They focus on categorizing risks based on estimated probabilities and impacts, often derived from historical data or expert judgment.

Definitions

Risk Matrix: A tool used in risk assessment to plot the likelihood of different risks occurring against the severity of their consequences. Typically, a risk matrix uses a two-dimensional grid where one axis represents the probability of occurrence and the other represents the impact or severity of the consequence.

Uncertainty: In the context of risk assessment, uncertainty refers to the lack of complete certainty about the likelihood and impact of potential risks. It can arise from limited data, variability in processes, and unknown future events.

Different Approaches

Traditional Risk Matrix:

- Axes: The x-axis usually represents the likelihood or probability of a risk event, while the y-axis represents the consequence or impact of that event.

- Categories: Risks are categorized into cells within the matrix, often color-coded (e.g., green for low risk, yellow for medium risk, red for high risk).

- Simplification: Traditional risk matrices simplify risk by assigning discrete categories to both likelihood and impact, which can hide the nuances of uncertainty.

Alternative Visualization Tools:

- Bubble Diagrams: These incorporate the dimension of uncertainty by varying the size of the bubbles based on the level of uncertainty associated with each risk.

- Risk Plots: These use three dimensions to visualize risks, adding a z-axis to represent the strength of knowledge or uncertainty, thereby providing a more comprehensive view of risk.

Alternatives and Discussion

Traditional Risk Matrices and Uncertainty:

- Representation of Uncertainty: Traditional risk matrices generally do not visualize uncertainty. They focus on categorizing risks based on estimated probabilities and impacts, often derived from historical data or expert judgment. This method assumes a certain level of precision and certainty in these estimates, which might not always be justified.

- Hidden Uncertainties: As noted by Aven (2009), traditional risk matrices often hide uncertainties in the background. The fixed categories for likelihood and impact do not reflect the variability or confidence levels in the risk estimates. For example, a risk event placed in a “high likelihood, high impact” cell might actually have significant uncertainty regarding its probability, but this nuance is not captured.

- Simplification Issues: According to Cox (2008), one major issue with risk matrices is their potential to oversimplify complex risk landscapes. By not visualizing the uncertainty, decision-makers might be misled into believing that the risk assessments are more precise and certain than they are. This can lead to suboptimal risk management decisions.

- Risk Communication: Traditional risk matrices are useful for quickly communicating risk levels to non-experts. However, the lack of explicit uncertainty representation can lead to overconfidence in the risk assessments. As highlighted by Bostrom and Löfstedt (2003), effective risk communication requires not only presenting the risk levels but also conveying the confidence (or lack thereof) in these assessments.

Alternatives Providing Better Visualization of Uncertainty:

- Bubble Diagrams: As suggested by Abrahamsen et al. (2011), bubble diagrams improve traditional risk matrices by visually representing the uncertainty through the size of the bubbles. Larger bubbles indicate higher uncertainty, thus providing a clearer picture of the risk landscape.

- Risk Plots: Aven (2013) proposes risk plots that use a third dimension to show the strength of knowledge or uncertainty, making it possible to see not only the risk level but also how confident the assessors are about these levels.

Conclusion

Traditional risk matrices have significant limitations in visualizing uncertainties. They primarily focus on categorizing risks based on fixed likelihood and impact values, often ignoring the confidence levels or variability in these estimates. This can lead to a false sense of precision and potentially mislead decision-makers. Alternatives like bubble diagrams and risk plots offer more nuanced visualizations by incorporating uncertainty directly into the graphical representation, thereby providing a more accurate and comprehensive view of the risk landscape. Decision-makers should be aware of these limitations and consider using enhanced visualization tools to better capture and communicate the uncertainties inherent in risk assessments.

Question 11-4: Discuss the role of a risk matrix as a communication tool.

Definitions

Risk Matrix: A visual tool used in risk management to assess and communicate the likelihood and impact of various risks. It typically features a two-dimensional grid where one axis represents the probability of a risk event occurring and the other axis represents the severity of its impact.

Communication Tool: In the context of risk management, a communication tool is a method or medium used to convey risk information to stakeholders, including management, employees, and external parties, to facilitate understanding and decision-making.

Different Approaches

Traditional Risk Matrix:

- Simplicity and Accessibility: The traditional risk matrix uses a grid to plot risks, with categories often colour-coded to indicate different levels of risk (e.g., green for low risk, yellow for medium risk, red for high risk).

- Ease of Use: It is straightforward and easy to understand, making it accessible to non-experts and effective for quick communication.

Enhanced Visualization Tools:

- Bubble Diagrams: These diagrams incorporate a third dimension (bubble size) to represent the level of SoK, providing a more comprehensive view of risks.

- Risk Plots: These plots use three dimensions to show probability, impact, and the SoK, offering a deeper insight into the risks being assessed.

Discussion

Advantages

Clarity and Simplicity:

- Ease of Interpretation: One of the primary strengths of a risk matrix is its simplicity. It provides a clear and concise way to visualize risk levels, making it easy for stakeholders to quickly grasp the risk landscape without needing extensive technical knowledge.

- Visual Impact: The use of colour coding (e.g., green, yellow, red) helps to immediately highlight high-risk areas that require attention. This visual impact can be effective in drawing focus to critical issues during discussions or presentations.

Standardization:

- Consistency: Risk matrices offer a standardized method for risk assessment across different projects and departments. This consistency is crucial for ensuring that all stakeholders are on the same page and that risks are assessed and communicated uniformly.

- Benchmarking: Standardized risk matrices can also facilitate benchmarking against industry standards or past performance, helping organizations to track improvements or identify recurring issues.

Decision-Making:

- Prioritization: By categorizing risks into different levels, a risk matrix helps decision-makers prioritize which risks need immediate action and which can be monitored over time. This prioritization is essential for effective resource allocation.

- Strategic Planning: Risk matrices can support strategic planning by providing a clear overview of potential threats and opportunities, thus enabling informed decision-making.

Disadvantages:

- Oversimplification: One major limitation of traditional risk matrices is the potential for oversimplification. By reducing risks to simple categories, important nuances and uncertainties may be overlooked, leading to incomplete risk assessments.

- Hidden Uncertainties: Traditional risk matrices do not explicitly represent uncertainties, which can mislead stakeholders into believing that the risk assessments are more certain than they are. This lack of transparency regarding uncertainties can be problematic in decision-making.

Enhanced Communication Tools:

- Bubble Diagrams and Risk Plots: These tools address some of the limitations of traditional risk matrices by incorporating uncertainty and the strength of knowledge into the visualization. While they are more complex, they provide a more accurate and comprehensive view of the risk landscape.

Conclusion

The risk matrix is a popular communication tool in risk management due to its simplicity, clarity, and ability to standardize risk assessments. It aids in prioritizing risks and supporting strategic decision-making. However, its limitations, such as oversimplification and lack of explicit representation of uncertainties, must be acknowledged. Enhanced tools like bubble diagrams and risk plots offer more detailed visualizations and can provide better insights into the risk landscape. Ultimately, while traditional risk matrices are useful for quick and accessible communication, they should be supplemented with more nuanced tools to ensure comprehensive risk assessment and informed decision-making.

Question 11-5: Draw the SEIPS model and explain the interactions by some examples.

SEIPS Model (Systems Engineering Initiative for Patient Safety): A framework designed to improve patient safety and healthcare quality by analyzing and optimizing the interactions between various components of the healthcare system. The SEIPS model considers the sociotechnical system, which includes people, tools, tasks, environment, and organizational structures.

Examples of SEIPS Model Interactions

Example 1: Implementing a New Surgical Checklist

- Person: Surgeons, nurses, and anesthesiologists need to understand and consistently use the checklist.

- Tool: The checklist itself must be clear, concise, and easily accessible during surgeries.

- Task: Incorporating the checklist into the surgical workflow without causing delays or disruptions.

- Environment: The operating room must be organized in a way that allows easy access to the checklist and minimal distractions.

- Organization: Hospital policies should mandate the use of the checklist and provide training to ensure compliance.

Example 2: Reducing Patient Falls in a Hospital

- Person: Nurses and aides need to be vigilant and aware of patients at high risk of falls.

- Tool: Use of bed alarms and non-slip footwear for patients.

- Task: Regularly checking on high-risk patients and ensuring their environment is safe.

- Environment: Ensuring patient rooms are free of obstacles and well-lit.

- Organization: Implementing hospital-wide fall prevention programs and policies, including staff training and regular audits.

Conclusion

The SEIPS model provides a comprehensive framework for understanding and improving patient safety and healthcare quality by analyzing the interactions between people, tools, tasks, environment, and organizational structures. By considering these interactions, healthcare organizations can design more effective systems that enhance safety and efficiency.

Question 11-6: It is well known that investments in new safety measures do not always give the intended effect, as new safety measures are sometimes offset by behavioural changes. To what extent are ‘behavioural changes’ incorporated in the SEIPS model?

Definitions

SEIPS Model (Systems Engineering Initiative for Patient Safety): A framework that emphasizes the interactions between different components of the healthcare system, including people, tools, tasks, environment, and organizational structures, to improve patient safety and healthcare quality.

Different Approaches

Traditional Approaches to Safety Measures:

- Focus on Individual Components: Traditional safety measures often focus on individual components such as technology or procedures without fully considering how these interact with human behavior.

- Assumption of Rational Behavior: Many traditional approaches assume that individuals will always use new safety measures as intended, without accounting for potential compensatory behaviors.

SEIPS Model:

- Holistic View: The SEIPS model takes a holistic view, emphasizing the interdependence of various system components, including how new safety measures interact with human behavior.

- Integration of Human Factors: By integrating human factors engineering, the SEIPS model explicitly considers how people interact with tools, tasks, and environments, thereby incorporating behavioral changes into the design and evaluation of safety measures.

Discussion

Behavioral Changes in the SEIPS Model:

- Person (Human Behavior):

- Role of Human Factors: The SEIPS model recognizes that healthcare workers’ behavior can significantly impact the effectiveness of safety measures. For example, if a new safety device is cumbersome to use, staff might bypass it, leading to potential safety risks.

- Training and Awareness: To address behavioral changes, the model emphasizes the importance of proper training and continuous education to ensure that staff understand and correctly use new safety measures.

- Tools and Technology:

- Usability and Design: The SEIPS model highlights the importance of designing tools and technologies that are user-friendly and fit seamlessly into existing workflows. Poorly designed tools can lead to workarounds or non-compliance, negating the intended safety benefits.

- Feedback Mechanisms: Incorporating feedback mechanisms within tools to monitor how they are used and to identify any unintended behavioral changes can help in making necessary adjustments.

- Tasks:

- Task Integration: The model considers how new safety measures fit into the overall task environment. If new measures complicate tasks or increase workload, staff may develop alternative behaviors to maintain efficiency, sometimes at the cost of safety.

- Workflow Optimization: Ensuring that safety measures are integrated into tasks in a way that supports rather than hinders workflow is crucial. This involves iterative testing and refinement based on user feedback.

- Environment:

- Physical and Social Environment: The SEIPS model considers the impact of the physical layout and social dynamics of the work environment on behavior. For instance, crowded or poorly organized spaces can lead to shortcuts or non-compliance with safety measures.

- Culture of Safety: Promoting a culture that prioritizes safety and encourages compliance with safety measures is essential. This includes leadership support and positive reinforcement for safe behaviors.

- Organization:

- Policies and Procedures: Organizational policies must support the intended use of safety measures and address potential behavioral changes. This includes clear guidelines, accountability structures, and regular monitoring.

- Continuous Improvement: The SEIPS model advocates for a continuous improvement approach where the impact of new safety measures is regularly evaluated, and adjustments are made based on observed behaviors and outcomes.

Examples of Behavioral Changes in SEIPS

Example 1: Hand Hygiene Compliance:

- Behavioral Change: Despite the availability of hand sanitizers, compliance with hand hygiene protocols can be low due to time pressure or forgetfulness.

- SEIPS Integration: The model would address this by ensuring hand sanitizers are conveniently located (environment), providing training and reminders (person), incorporating hand hygiene into the workflow (task), using automatic dispensers that provide feedback (tool), and enforcing policies that prioritize hand hygiene (organization).

Example 2: Use of Safety Checklists:

- Behavioral Change: Staff might skip parts of a safety checklist under time constraints.

- SEIPS Integration: The model would ensure the checklist is concise and integrated into electronic health records (tool), train staff on the importance of each item (person), simplify the task by embedding the checklist into the workflow (task), place reminders in key locations (environment), and create a culture that values thoroughness (organization).

Conclusion

The SEIPS model incorporates behavioral changes by emphasizing the interactions between people, tools, tasks, environments, and organizational structures. It acknowledges that new safety measures can lead to unintended behavioral changes and designs systems to minimize these effects. By focusing on human factors, usability, workflow integration, supportive environments, and organizational culture, the SEIPS model provides a comprehensive approach to ensuring that safety measures achieve their intended effects. This holistic perspective is crucial for addressing the complexities of human behavior in healthcare settings.

Question 11-7: Some experts highlight that new safety measures may crowd out existing measures. To what extent is this aspect incorporated in the SEIPS model?

Definitions

Crowding Out: In the context of safety measures, crowding out refers to the phenomenon where the introduction of new safety measures leads to the neglect, abandonment, or reduction in the effectiveness of existing measures.

SEIPS Model (Systems Engineering Initiative for Patient Safety): A framework designed to improve patient safety and healthcare quality by analyzing and optimizing the interactions between various components of the healthcare system. The SEIPS model includes people, tools, tasks, environment, and organizational structures, all of which are considered in a sociotechnical system context.

Different Approaches

Traditional Approaches to Safety Measures:

- Focus on Individual Measures: Traditional approaches often introduce new safety measures without fully considering their impact on existing measures or the overall system.

- Isolated Implementation: New measures are sometimes implemented in isolation, leading to unintended consequences such as crowding out of existing measures.

SEIPS Model:

- Holistic and Integrated Approach: The SEIPS model takes a holistic view, considering the interactions between new and existing safety measures and their impact on the entire system.

- Systems Thinking: It emphasizes systems thinking, ensuring that any changes or additions are evaluated within the context of the existing system to prevent crowding out and other negative effects.

Discussion

Crowding Out in the SEIPS Model:

Person (Healthcare Workers):

- Cognitive Load: The SEIPS model recognizes that healthcare workers have limited cognitive resources. Introducing new safety measures can increase cognitive load, potentially leading to neglect of existing measures.

- Training and Competence: Continuous training is essential to ensure that staff can manage both new and existing measures. The model incorporates ongoing education to maintain competence across all safety protocols.

Tools and Technology:

- Integration and Usability: The SEIPS model emphasizes the importance of integrating new tools with existing ones. Poor integration can lead to inefficiencies and the crowding out of older tools that may still be effective.

- Compatibility: Ensuring that new technology is compatible with existing systems is crucial. The model advocates for thorough testing and iterative refinement to achieve seamless integration.

Tasks:

- Workflow Impact: Adding new tasks related to new safety measures can disrupt existing workflows. The SEIPS model considers how new tasks fit into the overall workflow and seeks to optimize task design to prevent disruption.

- Task Redundancy: The model encourages evaluating whether new tasks duplicate existing ones and, if so, finding ways to streamline processes to avoid redundancy and ensure all safety measures are effective.

Environment:

- Physical Space: The SEIPS model examines how new measures affect the physical environment. For example, installing new equipment might crowd physical space, making it harder to access older, yet essential tools.

- Ergonomic Design: The environment must support the use of both new and existing measures. The model stresses the importance of ergonomic design to facilitate easy access and use of all safety measures.

Organization:

- Policy and Procedures: Organizational policies should support the coexistence of new and existing safety measures. The SEIPS model promotes policies that encourage comprehensive safety management, including regular reviews and updates to ensure no measures are inadvertently crowded out.

- Resource Allocation: Effective resource allocation is crucial to support both new and existing measures. The model includes strategies for ensuring that financial, human, and material resources are adequately distributed.

Examples of Crowding Out in SEIPS

Example 1: Implementation of a New Electronic Health Record (EHR) System:

- Crowding Out Risk: The introduction of a new EHR system could lead to less focus on maintaining paper-based records or existing digital systems.

- SEIPS Integration: The model would ensure that the EHR system is fully integrated with existing documentation practices and that staff are trained to use both systems efficiently. It would also assess the impact on workflows to prevent neglect of essential older records.

Example 2: New Infection Control Protocols:

- Crowding Out Risk: New infection control measures might reduce adherence to established hygiene practices if they are not well integrated.

- SEIPS Integration: The model would consider how new protocols fit with existing hygiene practices, ensure compatibility, and provide comprehensive training to healthcare workers to maintain high standards across all measures.

Conclusion

The SEIPS model incorporates the aspect of new safety measures potentially crowding out existing measures by emphasizing a holistic, systems-thinking approach. It ensures that any new measures are carefully integrated with existing ones, considering the cognitive load on healthcare workers, the compatibility and usability of tools, the impact on tasks and workflows, the physical environment, and organizational policies. By addressing these factors, the SEIPS model aims to prevent the unintended consequences of crowding out and to maintain the effectiveness of all safety measures within the healthcare system.

Question 11-8: Discuss what the consequences are for the evaluation of the effects of a safety measure, if one does not take into consideration that the resources available for safety measures are scarce.

Discussion and Conclusion

Ignoring resource scarcity in the evaluation of safety measures can lead to unrealistic expectations, misallocation of resources, unintended negative impacts, and reduced sustainability of safety improvements. Conversely, considering resource constraints results in more practical and feasible evaluations, better resource allocation, and sustainable safety enhancements. By acknowledging the limitations and strategically allocating resources, organizations can implement safety measures that are both effective and sustainable, maximizing the overall safety outcomes within their constraints. This holistic approach is crucial for achieving long-term improvements in safety standards.

Leave a Reply